I don't know about you, but I don't think we're really safe unless we have at least 10,000 more of these...

60 years ago the United States did this. Many believe it was necessary to defeat the Japanese. I do not. I feel like it was the moral low point of the United States. I base that opinion on the words of prominent members of the military at the time and those of members the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. I actually had to explain this position recently in a paper I wrote on the subject. I posted excerpts of it below in case anyone is interested. (I have edited the footnotes for length and because the quotes from military leaders are part of the public record and many notes were based on these three sources: Ronald Takaki’s Hiroshima, the movie Atomic Cafe, and a professor's class handout book.)

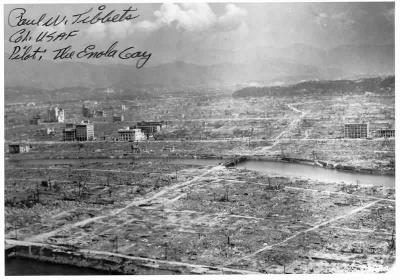

60 years ago the United States did this. Many believe it was necessary to defeat the Japanese. I do not. I feel like it was the moral low point of the United States. I base that opinion on the words of prominent members of the military at the time and those of members the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. I actually had to explain this position recently in a paper I wrote on the subject. I posted excerpts of it below in case anyone is interested. (I have edited the footnotes for length and because the quotes from military leaders are part of the public record and many notes were based on these three sources: Ronald Takaki’s Hiroshima, the movie Atomic Cafe, and a professor's class handout book.)BTW, since Hiroshima the US has conducted 1,054 atomic tests and has constructed over 10,000 nuclear weapons. There are thought to be over 22,000 nuclear weapons in the world today- all vastly superior to the one that caused the above devastation- enough to destroy the Earth three times over.

Happy reading…

… Admiral William D. Leahy, among others in the military, knew that Japan was already crumbling; “The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.” According to Rear Admiral Richard Byrd, “every officer in the Fleet knew that Japan would eventually capitulate.” General Dwight D. Eisenhower agreed saying he had “grave misgivings” about the use of the bomb against an enemy that “was already defeated.”

The Japanese were “already defeated” because the United States had orchestrated massive firebombing campaigns that absolutely devastated Japanese cities. In Tokyo alone over 1 million homes were destroyed, 17 miles of the ancient city were reduced to ashes, and between 60,000 and 100,000 people were killed. During the firebombing campaign the temperature in Tokyo was 2000 degrees Celsius, so hot that people would spontaneously burst into flames. Those who sought refuge in the rivers surrounding the town were boiled alive. A police officer in Japan described the streets as “rivers of fire. Everywhere one could see flaming pieces of furniture exploding in the heat, while the people themselves blazed like match sticks. . . . Immense vortices rose in a number of places, swirling, flattening, sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire.”

According to Fleet Admiral Ernest J King, the Japanese were in “disarray,” cut off from food, oil, machinery, and even their own troops in Manchuria by an “effective naval blockade” that would have soon “starved them into submission.” In fact, a report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff meeting in Potsdam in August 1945 stated the US had destroyed “25% to 50% of the built up area of Japan’s most important cities.” The report actually warned, “Prepare for sudden collapse of Japan.”

The effectiveness of the blockades and the firebombings and the fact that the Japanese had put out “peace feelers” led many to believe the war was coming to a close. General Lemay thought the war would have been over in “two weeks,” and by the latest October 1945, without the need for a U.S. invasion. Admiral King, General Arnold, Admiral Leahy and General Dwight Eisenhower, all joined Lemay in agreement and felt the Japanese were on the “verge of collapse.”

These were the best military minds of the time and they all saw the same thing: Japan was not capable of withstanding an invasion, she was about to crumble on her own and therefore there was certainly no need for the atomic bomb. According to Admiral William Leahy, there was not even a need for an invasion: “I was unable to see any justification, from a national defense point of view, for an invasion of an already thoroughly defeated Japan.” If Japan was already “thoroughly defeated,” and there was no need for an invasion according to the best military minds in the U.S., then a reasonable conclusion is the atomic bombings had little to do with saving America lives. In light of what the military leaders were saying as well as looking at how quickly the bombs were actually dropped, it is safe to deduce that the use of the atomic bombs was to end the war quickly, and stop the Soviets.

…

By July 1945, President Truman wanted to avoid the Russians from entering the war, a reversal of U.S. position from the previous year. There was a great fear that once the Soviets entered the war, they would have leverage at the post-war table and increase their “sphere in the region.” The Russian entry date into the war was fast approaching because Truman had been pushing the Japanese to accept “unconditional surrender,” an unacceptable position for the Japanese who feared for the life of Emperor Hirohito. Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew explained that the U.S. lost nothing by letting the Japanese keep the emperor and that the Japanese would surrender immediately if they were allowed to “save face.” Admiral Leahy agreed and feared Truman’s stubborn position would only prolong the conflict and was unnecessary. Truman was open to the idea of concession until the successful atomic test at Alamogordo in July 1945. Although Truman was advised that the Japanese would prolong the conflict to protect the emperor, he refused to accept any conditions for surrender after the test, even though the August 8 date of Russian entry was fast approaching. The test proved that no concession was necessary and the July 26 Potsdam Declaration made that point clear to Japan. The Japanese would submit to “unconditional surrender” or face “utter devastation.”

This arrogance again calls into question the morality behind the atomic bombings, especially when considering that the Japanese were eventually allowed to keep their emperor after the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It mirrors the arrogance reflected in keeping the Russians out of the war simply to avoid letting them sit at the post-war table. According to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Secretary of State James Byrnes considered the bomb a bargaining chip “in his pocket” that he could use to negotiate with the Russians. Byrnes was deeply wary of what would happen if the “Red Army entered Manchuria.”

Byrnes was a very influential fellow, not just as Secretary of State but also as the President’s representative on the Manhattan Project Interim Committee. His relationship with FDR gave him a lot of leverage on the committee whose “charge was to advise the president on the use of the bomb.” Byrnes, once considered FDR’s “assistant president,” also had a lot of leverage directly with President Truman, a man completely in the dark about the Manhattan Project until after he took office following FDR’s death in April 1945.

According to Takaki, Byrnes was “the single most important member (of the interim committee) promoting the proposal for a surprise attack.” Byrnes even argued against the common practice of dropping warning leaflets on the Japanese for fear that American POW’s would be moved toward the target or that a possible “dud” would only strengthen the resolve of the enemy. A warning would also take away the element of surprise with concern to the Russians; “The demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia with America’s military might.”

Because U.S. air raids had reduced most of Japan’s cities to “rubble and ruin” a true demonstration of the bomb’s awesome magnitude could not be known unless it was detonated over a “virgin target.” A city of 350,000 Hiroshima had been spared in the air raids and was targeted. Truman told Secretary of War Stimson to use the bomb on a “purely military” target, but Hiroshima was almost completely a civilian center, only its small communications center could qualify as a military target.

On August 6, 1945, 70,000 people would be wiped out instantly by Byrnes’ “bargaining chip.” More than 150,000 would later die from horrific injuries and radiation from the bomb. Hiroshima had been “completely wiped out.” ... Although Byrnes was “anxious to get the Japanese affair over with before the Russians got in,” he could not prevent it completely, and two days after Hiroshima, Russia entered the war. The following day, two days ahead of schedule, a second atomic weapon obliterated another civilian city, Nagasaki. Another 70,000 people wiped out of existence instantly.

If the first bombing was unnecessary militarily, than Nagasaki was downright criminal carelessness, especially in light of the fact that that bombing was advanced by two days. “What we did not take into account … was that the destruction [from the first bomb] would be so complete,” General Marshall explained. It would take Tokyo at least a day, “maybe longer,” to get the facts down on what had just occurred. When Emperor Hirohito heard the news of Hiroshima he was ready to “bow to the inevitable” and surrender, but because the total devastation slowed communications and assessment, he had no time to react before Nagasaki was attacked.

According to Takaki, Byrnes “clearly connected the atomic attack on Japan to the need to challenge Soviet expansionism,” and was willing to “drop the bomb on Japan in order to intimidate Russia.” Byrnes’ hawkish approach impressed Truman who said he was “able” and “conniving,” but also a man with “a keen mind.” Byrnes saw hostilities with the Soviets through a “frontier mentality,” adding, “He saw the war against Japan as a hunt, and he wanted Russia to stay out of it.” The atomic bomb would bring about a quick end to the war and Russia would not “get in so much on the kill.” (My Italics)

Admiral Leahy saw the use of the “barbarous weapon” as giving the U.S. “no material assistance” in winning the war against Japan. Leahy claimed Japan was “already defeated and ready to surrender” and that the bombings represented “a modern type of barbarism not worthy of Christian men.” Secretary Stimson agreed, first asking for a warning to the Japanese and arguing against the predominant racial stereotypes that were “deeply embedded in the minds of influential people in the State Department.” Stimson said the war was prolonged as a result of the United States’ demands for unconditional surrender. He argued for “continuance” of the throne at Potsdam, but “The President and Byrnes struck that out.” According to Takaki, the effect of that decision led to “the vaporization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Sadly, US policy towards Japan after the bombings allowed for the continuance Stimson advocated for. … For Stimson, the bombings were not as simple as saving American lives, but rather preventing a war with Russia.

However fruitful the post-war table turned out to be, the decision to incinerate two civilian populations to end a war that was going to end itself in a matter of “weeks” is morally reprehensible. As Secretary Stimson stated in February 1945, U.S. policy “never has been to inflict terror bombings on a civilian population.” But the policies of World War II changed tradition moral holdings, and the United States’ claim on a moral high ground was forever damaged. Philosopher Lewis Mumford has suggested the “urban crematoriums” created by U.S. firebombing campaigns were no different than the Nazi death camps. Secretary Stimson even asked at the time if the United States wanted a reputation of “outdoing Hitler,” with regards to its own atrocities.

...

For anyone who wants even more joy, my mom sent along an article by the priest who blessed the pilots who bombed Hiroshima. It is heavily religious, but very interesting, especially for those who find some contradictions in the dominionist cry that "We're a Christian nation!" as Stimson seemed to. There is also a fantastic documentary from the discovery channel film entitled Hiroshima: The First Weapon of Mass Destruction. Really, really sick stuff though, not for the squimish.

<< Home